"Why Make Art in Auschwitz?"

Lessons from my father on creativity, humanity, and our obligation to imagine

I was about twelve years old and distinctly remember my Pop sitting at our wooden kitchen table, drinking his morning coffee and reading the newspaper. It was an ordinary weekend, but a heavy question was on my young mind. It didn’t feel like a question I should ask—it felt insensitive, prying; perhaps I was too dumb to understand the answer; maybe there was no answer.

Curiosity, then as now, overpowered my hesitation, and I simply asked:

Why make art in Auschwitz?

Pop slowly put the paper down on the table and looked up at me, his green eyes sharp and tender against the contrast of a dark, thick beard and wild shoulder-length hair. He was a big man, tall and commanding, but inside he was a teddy bear with an artist soul. On brand for his humor (in an oft heard Mel Brooks Yiddish accent) and shaking his palms upward, he replied:

Vhat else is there to do—die!?

He would frequently make a joke before talking about genocide. As a kid, I didn’t yet grasp why adults turn trauma into humor… so, I shrugged.

Have a seat, sugar.

He always said that when he was about to drop some knowledge on me.

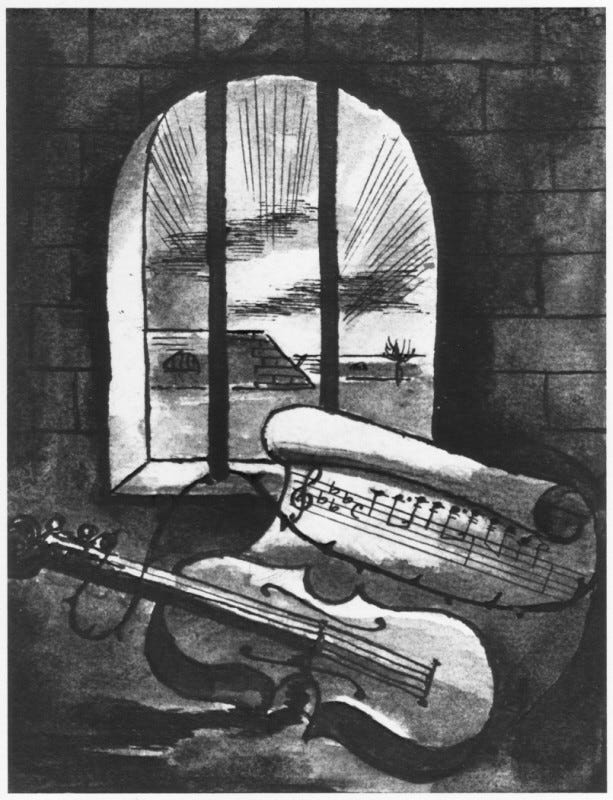

At the time I had just learned about the Auschwitz Women’s Orchestra, so he first explained that most of the music played during the Holocaust was not by choice, and was often overtly used as part of the process of mass death, in addition to the traditional uses of music as propaganda.

Pop said it was the same for other artists and creatives, inside and outside of the ghettos and camps, who were forced to use their skills to entertain and assist genociders while they destroyed all that was good and whole around them.

It wasn’t only Jewish artists that suffered this fate, all creatives in the path of Nazi Germany were targeted for use or death. Prior to the passage of the Nuremberg Laws in 1935 (transforming Jewish identity from a religion to a race) thousands and thousands of beautifuls minds were extinguished at the Dachau concentration camp, which opened two years before the laws became clearly fascist.

Dachau is one of the places the Nazis perfected their bureaucratic goals into an efficient, and cost-saving, process of mass murder and human disposal. As is well known, Nazi torture and death techniques were first tested on the disabled, the queer, the Roma, Soviet prisoners, intellectuals, political opponents, immigrants, and anyone deemed different enough.

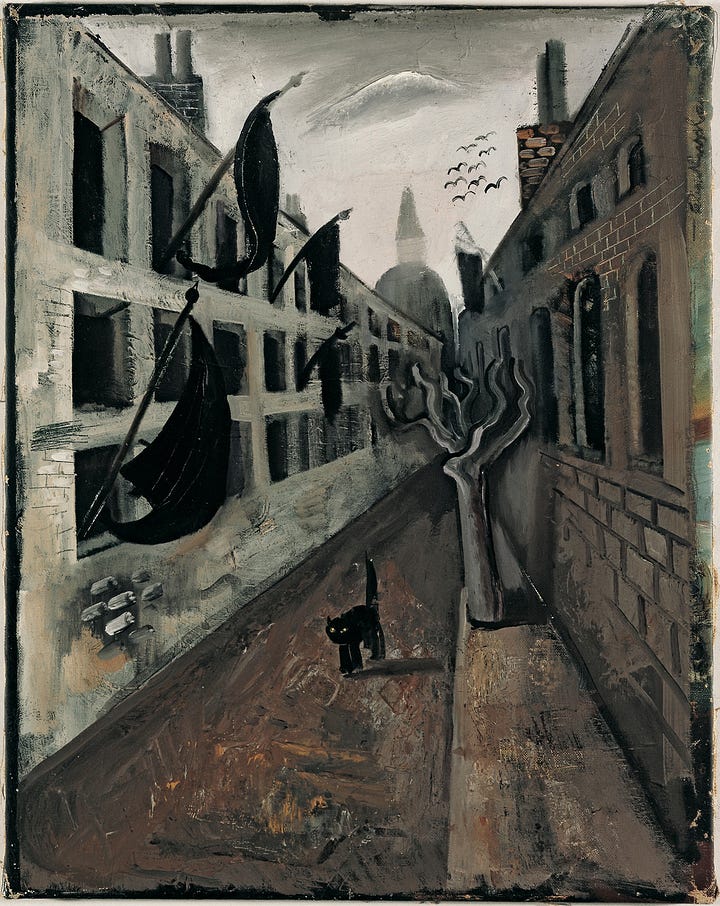

We also discussed art made in private, the pieces that reflect the truth of communal suffering. A sketch here, a poem there, and the amount of thought, planning, bargaining, and risk each creation must have cost. Pop described the art that took place secretly during the Holocaust as reclaimed moments of dignity. Imagination is the greatest tool of a free mind, he said.

As an artist, he believed (as I believe) that fascism steals individuality as a means to kill creativity. The end goal of all authoritarians is the destruction of imagination. If you can’t imagine something different, you can’t do anything different; you become frozen and dependent on the system to imagine for you. This means art created during times of mass destruction and death is crucial to nurture creativity and maintain human dignity.

Creative work and artistic expression are the ultimate problems of control for authoritarians. The problem is not only that artists are capable of imagining new things, it’s also how they encourage others to do the same. Every artistic expression has the power to change multiple minds; at the very least to plant an idea, that could one day sprout into an ideology.

It’s easy to kill one artist, it’s another matter entirely to kill the artistic spirit, something many artists believe is a gift from our connection to the Divine.

“I remember thinking in school how I would grow up and would protect my students from unpleasant impressions, from uncertainty, from scrappy learning... Today only one thing seems important — to rouse the desire towards creative work, to make it a habit, and to teach how to overcome difficulties that are insignificant in comparison with the goal to which you are striving.”

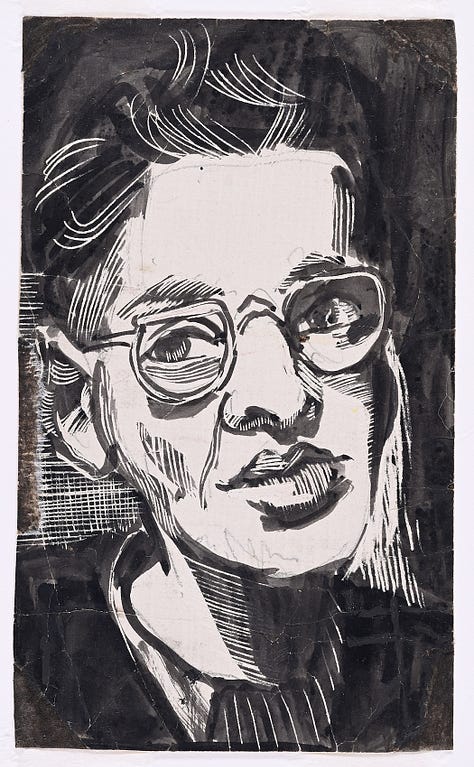

Friedl Dicker-Brandeis

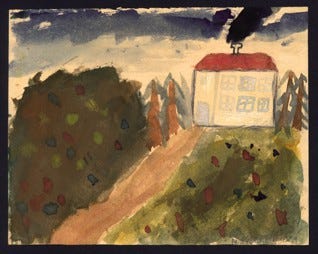

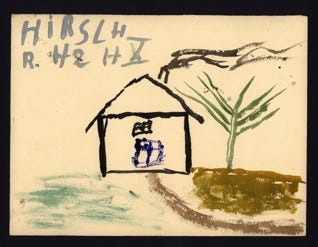

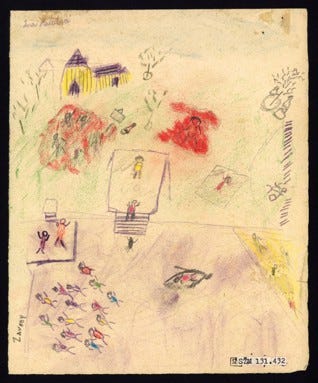

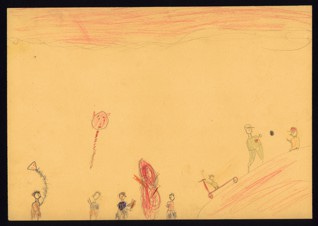

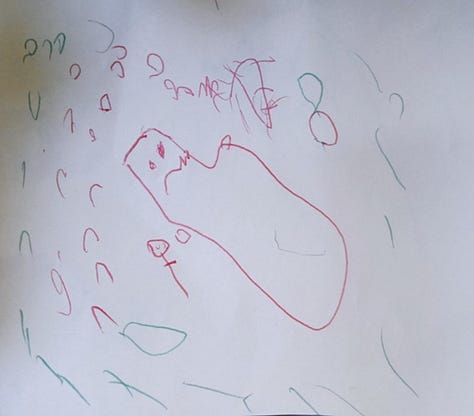

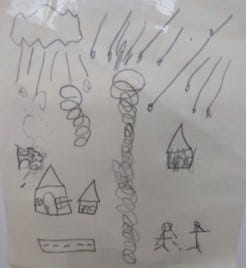

Austrian artist Friedl Dicker-Brandeis wrote the above in a 1940 letter to a friend, two years before she and her husband were deported to the Terezín Ghetto. There, she secretly taught children art as a way to express their trauma, keep their imagination alive, and help them cope before death.

Less than two years after being forced into the ghetto, Friedl boarded a train to Auschwitz II and was murdered in October of 1944. Before leaving Terezín, Friedl entrusted the art collections to a colleague that survived, and hide the art until it was safe to make it public. The extensive collection remains one of the largest and most haunting visual histories from the Holocaust.

(Links to this and other collections are at the bottom of the post)

My Pop first taught me about Friedl Dicker, Hannah Arendt, Primo Levi, Isaac Asimov, Marc Chagall, Howard Zinn, and many other Jewish artists who understood the immense, and fragile, power of creativity as a tool for communication and survival. And it was Pop who first taught me of Palestinian-American writer Edward Said, of children with rocks vs military tanks, and of a Holy Land, where the soil is rich in cultures, myths, and blood.

He warned me when I was teenager that Netanyahu’s vitriol racism against Palestinians would one day bring a reckoning against Jewish people and the Western imperialism so many have embraced. He warned me of the dangers in groupthink, when conformity comes wrapped as peace, and rational thought is discarded for comforting fiction. He warned me about many things.

I thought he was overly cautious and paranoid, like a lot of kids feel about their Jewish parents. I thought the world had changed, that we wouldn’t let things go back to the dark days of global fascism and multiple, concurrent genocides, or of never-ending suffering and despair.

My generation wouldn’t let Nazis march their way into our towns, terrorizing vulnerable minority communities.

My generation wouldn’t let authoritarians plunder national coffers to endlessly murder innocent civilians and call it National Security.

My generation wouldn’t let their friends and neighbors disappear into the void.

Americans wouldn’t vote for open fascists.

Jews wouldn’t support genocide.

HOLY FUCK, was I wrong.

And now, as I look around at current conditions, I miss Pop almost as much as I did in the first years after he died. But when I see the Star of David in the art of Palestine’s children, and I think of the hatred, violence and death it represents to Palestinians, I’m glad my father didn’t live long enough to considered whether or not to stop wearing it.

As a professional creative living in a world where Israel is committing a genocide against Palestinians, and a world where fascism is once again rising, I have a better understanding of the bigger picture Pop was trying to show me. I spend a lot of time reflecting on his wisdom and lessons, about what it means to be a patient and responsible person, what it means to value and act according to ethics and justice, and what it means to follow a creative path of dissent.

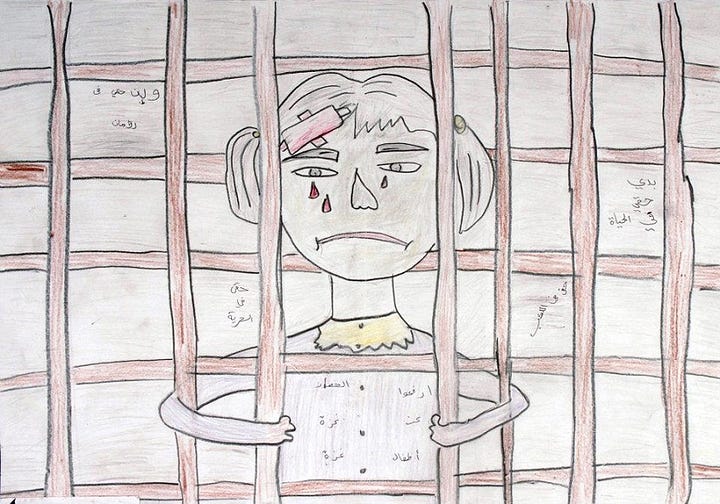

The exhaustion of authoritarianism robs us all of the precious energy we need to imagine and create a better future, as individuals and as a species. Nazism killed 3.5% of the world’s population, doing incalculable damage to humanity and imagination. The humanitarian fallout fueled by Nazis continues to shape our world today, one only has to look at the children’s art from Gaza to understand.

Expression is important because it’s a record of history. I’ve come to believe there is a natural-order responsibility for creatives to keep imagining new futures, even if we do not personally live to see them. Art, after all, is evidence of both the worst in humans, and the greatest possibilities we can imagine. The art of the world’s children is always a solid measurement for how we’re doing with our humanity.

Artists want more art to exist so the world can expand and grow into a better version. Fascists want more fascists to exist so the world can shrivel and decay into the past.

I want y’all to make art, because fuck fascism.

View more art created by Jewish children under Nazi rule, Palestinian children under Israeli rule, and adult artists during the Holocaust:

Prague Jewish Museum: Children’s Drawings from Terezín Ghetto Online Collection

Latam Art: Drawings by Palestinian Children Collection

UNRWA: Drawings from Three Palestine Refugee Siblings in Gaza

United Nations Online Exhibit: Responsibility for Memory: The Role of Art in Holocaust Remembrance

Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial: Art at Auschwitz, Online Collection and Education